Origins - Allevamento d'Egitto

Main menu

Origins

From the Roman Empire up to now

The origins of the Bergamasco Shepherd Dog date back to very long ago and unavoidably mix with those of many other European shepherd dog races.

he presence of its ancient predecessors is historically documented, over the whole Alpine Arch, by the time of the Roman Empire.

Historians of the time describe a dirty-white (in which it can be recognized the 'white coffee' color, technically defined 'Isabella'), long-haired dog used with great satisfaction by the Cisalpine populations to follow up the flocks and the herds at grass.

The caravans of the barbarians passing through the Alps caused the dispersion of this race, typical of those places, that was progressively replaced or crossed with others till its unjustified disappearance.

Since then it fell into oblivion, till the beginning of the XX century, when some passionate dog-lovers found a few specimens in the Bergamo Valleys.

It is only thanks to the traditional autonomy of the Bergamo people, jealously castled on their mountains, that the latest specimens of this mythical race kept on living, working and reproducing, and therefore avoided their extinction and gained the name of 'Bergamasco'.

The Bergamo Valleys, in fact, are to be considered, under this point of view, an authentic ecological niche.

The "Bergamini" and the Bergamo Shepherd Dog's work

The flow of the populations that came down from North Europe always avoided the bare and apparently desert Bergamo Valleys to use the more convenient and sunny way through Valtellina.

On their side, the inhabitants of the Bergamo Valleys, proud and untamed mountaineers, always preferred not to establish a contact with other populations and, for several centuries, perpetuated their usages and customs, totally impermeable for every external influence.

This fact itself, though, would not have been sufficient to save a canine race.

The other determinative factor was the intense and difficult work that this dog was called to do and that also caused a very severe selection, so severe that it created a particularly strong and stout race, but also careful and sensitive, able to practice an extremely difficult and exacting activity: that of conducting the herd to the inaccessible and insidious mountain pasture-lands.

For many centuries, till a few decades ago, the local economy was mainly based on agriculture. But, while on the mountains people's hard work was recompensed by lean harvests, in the byres of the lowlands a large quantity of cows was bred. With the arrival of Spring, though, it was necessary (if not indispensable) to conduct the cows to the alpine pastures, where they could find enough nourishment, therefore avoiding to impoverish the pastures of origin, used for various cultivations, surely more precious than grass.

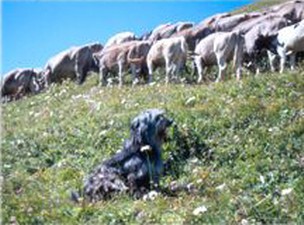

Consequently, in April, the only known Italian example of transhumating herdsmen, called 'Bergamini', used to go downhill and, helped by their irreplaceable dogs, gathered together herds of 6/700 heads, also called 'Bergamine', to take them, through a journey several weeks long, to the alpine pastures at the height of 2000 meters.

The tradition of the 'Bergamini' represents an extremely typical element of the Orobian culture.

They carried on with their activity, both on the Lombard and on the Swiss versant of the Alps without apparent distinctions. Normally used to live under the stars in conditions of great difficulty and labour, the 'Bergamini' where linked by very strong solidarity bonds.

Particularly, they had developed their own language, called 'Gaì', even more arduous than the almost incomprehensible 'Bergamasco' dialect; through it they comunicated and transmitted precious information on the accessibility of the mountain passes, on the possibility to find food and a place where to spend the night, and on how to smuggle goods of first necessity avoiding troubles with customs officers.

The life lead by the 'Bergamini' was extremely uncomfortable but, once chosen the route, the main part of the work was undertaken by the dogs that, untiringly going from the head to the tail of the herd and back, kept the cows together and guided them through difficulties and hazards day in, day out until the end of the season.

At night, then, it was always the dog's duty to make sure that the herd didn't scatter, as well as to guard against thieves and to face the most feared plunderer: the wolf.

Once reached the predestinated 'malga', the motory activity decreased, but the care should increase. Early in the morning, after the milking, the cows get out of the 'barech' (pen, also called 'stazzo'), situated nearby the 'malga' and must be lead to even more inaccessible pastures, which were therefore richer in grass; there they must be kept till the early afternoon, in spite of their reluctance to graze on steep grounds.

This kind of activity requires dogs with an extremely determined character and able to face danger with no hesitation. When the mountain tops are covered with clouds and storms come nearer, cows instinctively look for shelter in the woods surrounding the alpine pastures; while trotting, they risk to become lame down the precipituous slopes or, worse, to fall in a precipice.

In such occasions, that can occur both in the daytime and at night, a few dogs, naturally 'Bergamaschi', can be of fundamental importance by rapidly reaching the vanguards of the herd and, with a quick and sometimes violent frontal encounter, instantly stopping the run and bringing the herd back to the place chosen by the herdsman.

A dairyman always joined company with the 'Bergamini' in the 'malga', and his task was that of transforming the daily milked milk into the very typical 'Formai de Mut'.

The 'Branzi', the 'Taleggio' and the whole variety of 'malga' cheese are the results of his work.

Still today, the 'Bergamini' and their dogs, though partially substituted by the more convenient trucks, keep unaltered in those places working rhythms and ancient habits.

For definition, consolidated tradition and consequent selection, the Bergamo Shepherd Dog must be considered a cattle-dog, and not a sheep-dog as many erroneously think. This doesn't mean that the Bergamo Shepherd Dog cannot work with sheep too; on the contrary, a trained subject can lead indifferently any animal, from the typical Bergamo giant sheep to horses.

In particular, it turns out to be very important to exactly define its standards and its dimensions, surely more important than those normally attributed to sheep-dogs.

Characteristics of the breed

The 'Bergamasco' is a dog of medium size, the height at the withers ranging, in the male, from 60 to 62 cm, and in the female from 56 to 58 cm, but -not surprisingly just as a consequence of its being a cattle-dog- it can also be bigger.

Symptomatic of it is the fact that in the Novara national exhibition, held on the 12th of December 1930, a female called Lea, that was measured 63 cm at the withers, won the first prize.

Il colore degli occhi è scuro, come pure il tartufo ed i polpastrelli devono essere neri.

The most typical color of the coat is grey spotted, but the 'Zaino' black and the 'Isabella' (white coffee color) are equally recognized.

The color of the eyes is dark and, similarly, the truffle and the fingertips must be black.

The Bergamo Shepherd Dog, apart from conserving intact the shepherd's instinct, developed, in the solitude of the alpine pastures, a strong attachment to its owner, with whom it shared work, food and pallet.

The Bergamo Shepherd Dog is thus used to listen to his owner and quickly assimilates the orders it receives. Among the countless requirements of the sheep-breeding there is that of avoiding that the flocks or the herds trespass on cultivated fields or on private properties.

The Bergamo Shepherd Dog is therefore used to spot the different cultures and, in general, all of the signals that the ground gives. It is also attracted by borderlines and, running along a street or a path, it will tend to do it only on one of the two sides. The bit is a sort of complement to its capabilities, being it able to dose its intensity in an extremely precisely way and therefore resulting particularly reliable.

According to its character, it will always be friend and partner to man, and will never be a mere automaton. You will manage to teach it whatever you like, but you must take into consideration the possibility that it might refuse to obey to an unuseful order or to take initiatives of defence while you have never trained it to that purpose

It is however thanks to its proverbial adaptability that it will always stand by you, be it on a mountain top or at the foot of your bed.

Fur and shearing

Let's finally deal with the most discussed and debatable subject: the fur.

Being a mountain dog, the 'Bergamasco' is protected by an abundant fur. The work on the mountains is very tiring and it is indispensable to warrant the dog the greatest agility and lightness possible.

From time out of mind, all the dogs are shorn in Spring, so that they can face their whole working period fully freely; already at the end of the season, each of them will have produced enough hair to assure itself a warm and soft coat for the whole Winter.

This is a documented, consolidated and indisputable custom. The dogs are kept agile, clean and 'fresh' even under the sun of the 2000 meters.

The awfully bad custom of letting the fur grow till it crawles on the ground, apart from not being typical nor founded, is source of great discomfort and of illnesses for the dog, without having, however, any positive consequence.

Long hair remarkably reduces the dog's mobility, compromising some of its peculiar characteristics like agility and quickness. The dog's hygiene and cleanliness are seriously compromised too, and with them your pleasure to spend time with it.

To convince of this the ones of you that are still sceptical, I would suggest to widen our horizons and observe the whole family of the European long-haired dogs, from the Briard and the Bobtail.

Every nation claims that 'its' race is the one from which the others derived; maybe none of them is right, but it is certain that the various races are related and therefore similar. In fact, all of them produce a very fine underfur which naturally tends to felt and to form inextricable clots, that in the 'Bergamaschi' are called 'taccole'.

If the 'taccole' are not removed, they keep on growing causing unthinkable discomforts.

Our herdsmen, but also the French and the English ones, don't have the time to comb their dog's hair and provide for their toilet with periodical shearings, but none of them would dream of letting the fur grow to the ground, first of all because of the great respect they have for their dog.

Between a shearing and the next, effectively, the clotted fur can have its functionality, but solely if the hairs end up to assume a broad and flat shape -just like real tiles- and are thus able to play a generally protective role, and till it reaches the length of 8-10 cm.

This consideration, though, only applies to a dog that works and is exposed to danger, and it would be reasonless to think it does to a homey one too.

What is worse is that, if the fur is not shortened, it loses any use and eventually becomes an authentic 'broom' picking up dirt and excrements.

Getting more specific, it is important to add that the 'Bergamasco' is characterized by two types of fur: mainly goat-like on the front half of the body, and predominantly sheep-like on the second half. The goat-like fur is, according to its definition, bristly, and it doesn't felt; the presence of the 'taccole', thus, must be tolerated only on the second half of the body, where the prevalence of woolly hair favours the felting. Any excess of 'taccole' must not be considered a merit, but, on the contrary, a serious degeneration of the race.

Wandering about the French countryside, I personally saw more than a Briard covered with 'taccole', but no French is proud to propose a dirty dog and wants that at dog-shows it defiles clean and with its hair combed.

'La Provincia di Bergamo' (interesting handbook written by Luigi Re and published by Bolis in 1957) dedicates enough space to the 'Bergamasco' and presents it photographed with a flowing coat, without any 'taccola'.

The Official Bulletins of the Italian Kennel Club of the Twenties pictured dogs with a long and flowing hair, almost without 'taccole'. So why the 'Bergamasco' dogs, instead of clean and combed, defile awkwardly made heavy by horrible (and sometimes stinking) furs, always forced to exhibit their worst appearance?

At first people curiously go near the dog, but later on they inevitably get frightened by the not always edifying sight, and it is perhaps also for this reason that this race survives on the verge of extinction with a very low birth-rate, sad tail-light of the other European shepherd races. It would be worth wondering, however, what the reason for this exaggerated and unjustified hair is, particularly considering that it is a very recent phenomenon, just characterizing the last 20/30 years.

The answer I find more convincing is that it was never made an historical research on the 'Bergamasco', extended to its whole surrounding world, capable to fill in the knowledge blanks and from which you could infer the historical reality, but, on the contrary, people have always preferred to believe to the most eccentric and extravagant theories. Without an accurate study that can support with data and incontrovertible demonstrations the thesis that everyone has (too) freely divulged, all of the writings remain the mere opinions of the different authors, but cannot and must not condition the life either of the dog or of the race. This aesthetic 'liberty' not only is bad for the dog, but it also does not allow us to fully enjoy its great qualities.

I have asked for some time to Bergamo Shepherd Dog's owners to make a right and proper love gesture to their pets, as a mature and honest dog-lovers should, but I must say that my appeal still seems to be vain: the habit of maltreating the 'Bergamasco' letting the hair grow excessively is stubbornly and unbelievably deep-rooted, really difficult to eradicate.

My grandfather was a 'Bergamino', I am 50 and I live with 'Bergamaschi' since I was born, and I have been breeding and professionally selecting them for 30 years. My knowledge of the 'Bergamasco' is empiric, but definitely deep and wider than the one boasted by those who just pair them, without knowing anything about their life and history.

That's why, when I am asked what the main characteristics of the 'Bergamasco' are, I now answer: "the 'Bergamasco' is a long-haired dog but, if the hair is too long, that means that its owner takes no interest in it and treats it bad."

Something interesting

As I said, not much has been written about this obscure and noble protagonist of many pages of our history, but it is possible to find various quotations about it in people's memory. Oral tradition hands down innumerable tales that well convey information on this dog's nature, dog that not only was the Bergamo herdsmen's most reliable partner, but was also able to do countless duties with zeal and spirit of sacrifice worthy of man's best friend.

Oral tradition hands down innumerable tales that well convey information on this dog's nature, dog that not only was the Bergamo herdsmen's most reliable partner, but was also able to do countless duties with zeal and spirit of sacrifice worthy of man's best friend.

Amongst the numerous stories, the most famous is the one about the character of Pacì Paciana, 'ol Padrü de la Val Brembana', a sort of 'Passator cortese' who lived on brigandage in the second half of the Eighteenth century, freely making incursions all over the Bergamo Valleys.

Pacì Paciana -so the legend goes- pursued by policemen that had been chasing him for ages, adventurously managed to save his life by throwing himself from the Serina bridge into the Brembo river. His flight was tenaciously and bravely covered by his dog, naturally our 'Bergamasco', that remained on the bridge and faced the policemen, sacrificing its life to save his owner's.